As the first large scale design festival to go ahead in 2020 after COVID-19 shut down events around the globe, the London Design Festival (LDF) 2020, which ran from September 12-20, employed a new hybrid way of bringing the festival to life. In light of the obstacles and opportunities created by the events of the last year, the London Design Festival featured work that blends the physical and virtual, plays with the idea of connections in a time of distancing, and highlights the possibilities of a more sustainable future.

London Design Festival 2020 explored how art can bring us together, connecting viewers with each other and the environment.

The blended format for LDF 2020, which combined virtual events alongside physical ones, served to democratize the event, giving more people the ability to attend than ever before. As one of the main partners of the festival, the V&A Museum traditionally hosts a range of newly commissioned works. This year, they instead utilized digital tools to highlight favorite objects and galleries within the museum; every day during the festival, a member of the museum staff led a guided tour via Instagram, offering public access to the space. Adorno’s Virtual Design Destination also offered virtual viewing through a bespoke portal created to display real-world pieces in a digital environment. Visitors were shown collections of work in 14 country pavilions designed to showcase the collectable pieces, narrated by each country’s pavilion curator.

With the country-wide shutdown closing the doors to shared creative spaces and studios, artists were forced to reconsider how they use the spaces available to them and how to remain connected in a distanced world. A project from Central St Martins graduate students, who were tasked with designing at a distance for the last few months of their degrees, tackled the concept of space and positioned art as a tool for connection. Their work was displayed during LDF in a three-part digital show: New Languages of Making, which looked at forced material innovations; The Social and the Self in Isolation, which explored how our interactions with others changed during lockdown; and (De)constructing Space, which questioned people’s relationship with physical spaces.

Aiming to show the power of coming together while remaining socially distant, Unity by the French designer Marlene Huissoud allowed visitors to work together to create art. Her installation was powered by individual foot pumps, spaced six and a half feet apart, which visitors used to inflate the piece, watching it breathe and move as they interacted with it. Speaking of the purpose of the piece, Huissoud said, “this installation is more than an interactive piece, it’s for society to wake up and realize how vital it is for us to be united and act as a whole.”

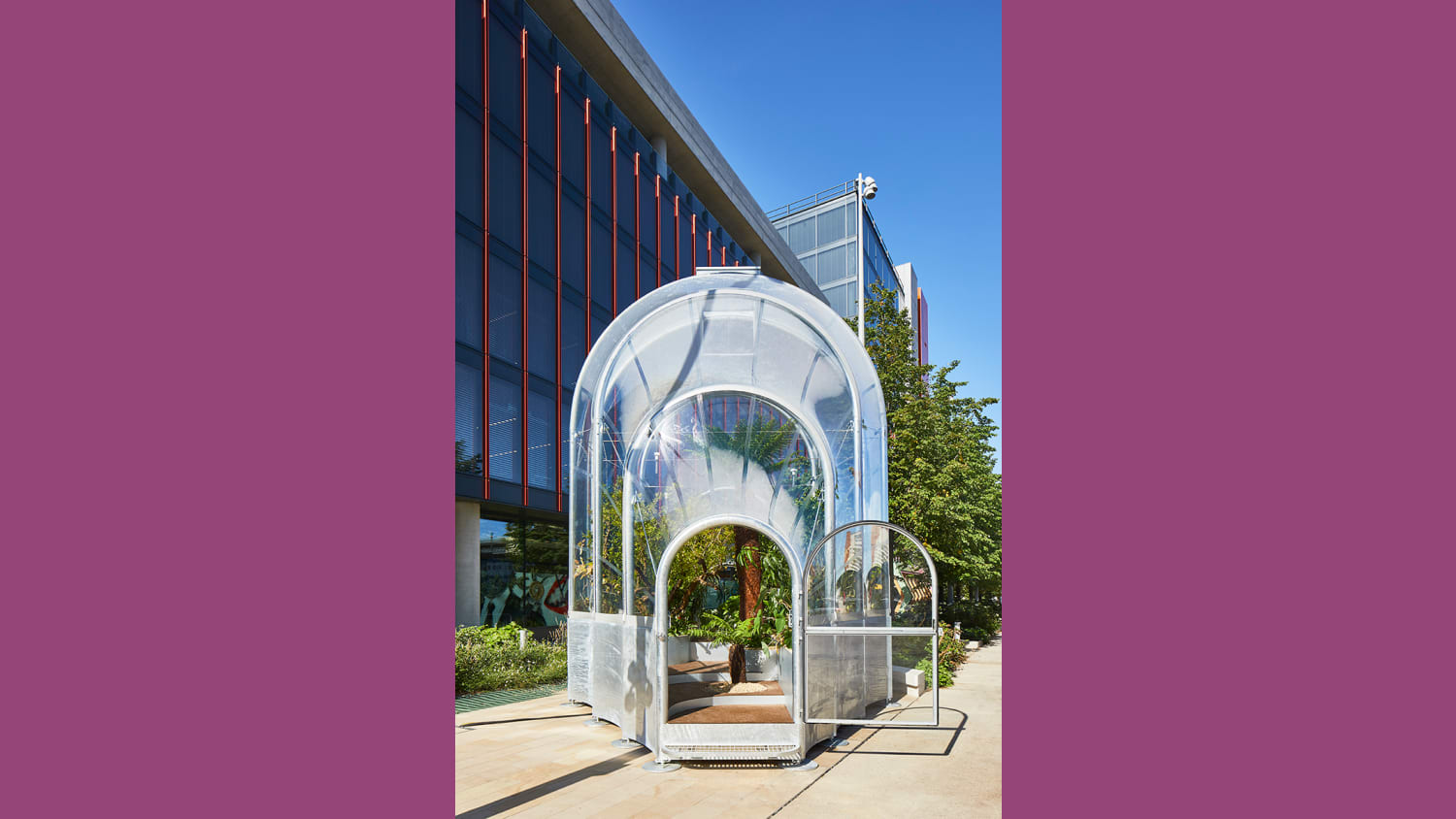

Although the pandemic may have temporarily dropped the sustainability conversation down the priorities list, it remains a crucial topic for designers in their push to ‘build back better’ for the future. The Hothouse, created by London-based Studio Weave in partnership with Lendlease and LCR, is a Victorian-inspired greenhouse that holds a variety of edible plants from around the world. All of the plants contained in The Hothouse could not grow in the UK now, but due to the effects of climate change, scientists predict they would all be viable by 2050. The structure will remain in place for a year and aims to educate visitors on how we could create a more sustainable future.

Also drawing attention to the natural environment, muf architecture/art transported five mature trees to positions in the Kings Cross Design District for their installation On Their Way. Resting on their sides, the trees are actually placed with their branches pointing along a temporary trail, leading visitors around the area. At the end of the festival, the trees will continue on their way to the Grove School, a local school for children with autism, to form an outdoor classroom.

There Project’s Designing National Park City, takes visitors on an audio adventure through the 200-year-old Regent’s Canal, inviting designers to think about the future of cities if they were designed for both people and wildlife. How would they look and feel different to our cities of today? With the canal already supporting a diverse ecosystem of wildlife and human residents, shaping a more equitable division of resources is achievable.

The festival highlighted the importance of working together to reconsider our shared environments—and how art can be used in service of social and ecological unity.

Please provide your contact information to continue.

Related Content

For Arriana Yiallourides “It’s No Longer About Selling Ideas, It’s About Creating Them Together”