US-based start-up Hereafter.ai, has been created not only as a way to talk with those who have died but positions itself more broadly as a way for people to “be remembered.” To use, one is sent interview prompts by a virtual chatbot, and then invited to record thoughts. Prompts include “a story that I remember from when my child was little is…,” and “when I’m gone, I would like to be remembered for….”

From AI avatars of loved ones who have died to conversations with the deceased via a chatbot—can tech create a form of life after death?

In China, meanwhile, people can create avatars of dead loved ones for as little as 20 yuan ($3 USD), the Guardian reports. Zhang Zeiwei, the founder of one Chinese AI firm, Super Brain, told the South China Morning Post that since he established the company in mid-2023, it has helped “thousands” of Chinese people “digitally revive” those who have died, using as little as 30 seconds of audiovisual material. The form of the avatars created by Super Brain can span a chatbot with a digital image, through to a 3D human model.

And at the more grandiose end of the griefbot spectrum, Chinese AI company SenseTime this year created an avatar of its late founder, Tang Xiao’ou, to address the company’s annual general meeting. While Tang had passed away in December 2023, his avatar was able to speak at the meeting in March 2024. MIT Technology Review reports that “at least half a dozen companies” in China are offering AI services that provide ways to interact with dead loved ones, which the publication describes as “the newest manifestation of a cultural tradition: Chinese people have always taken solace from confiding in the dead.”

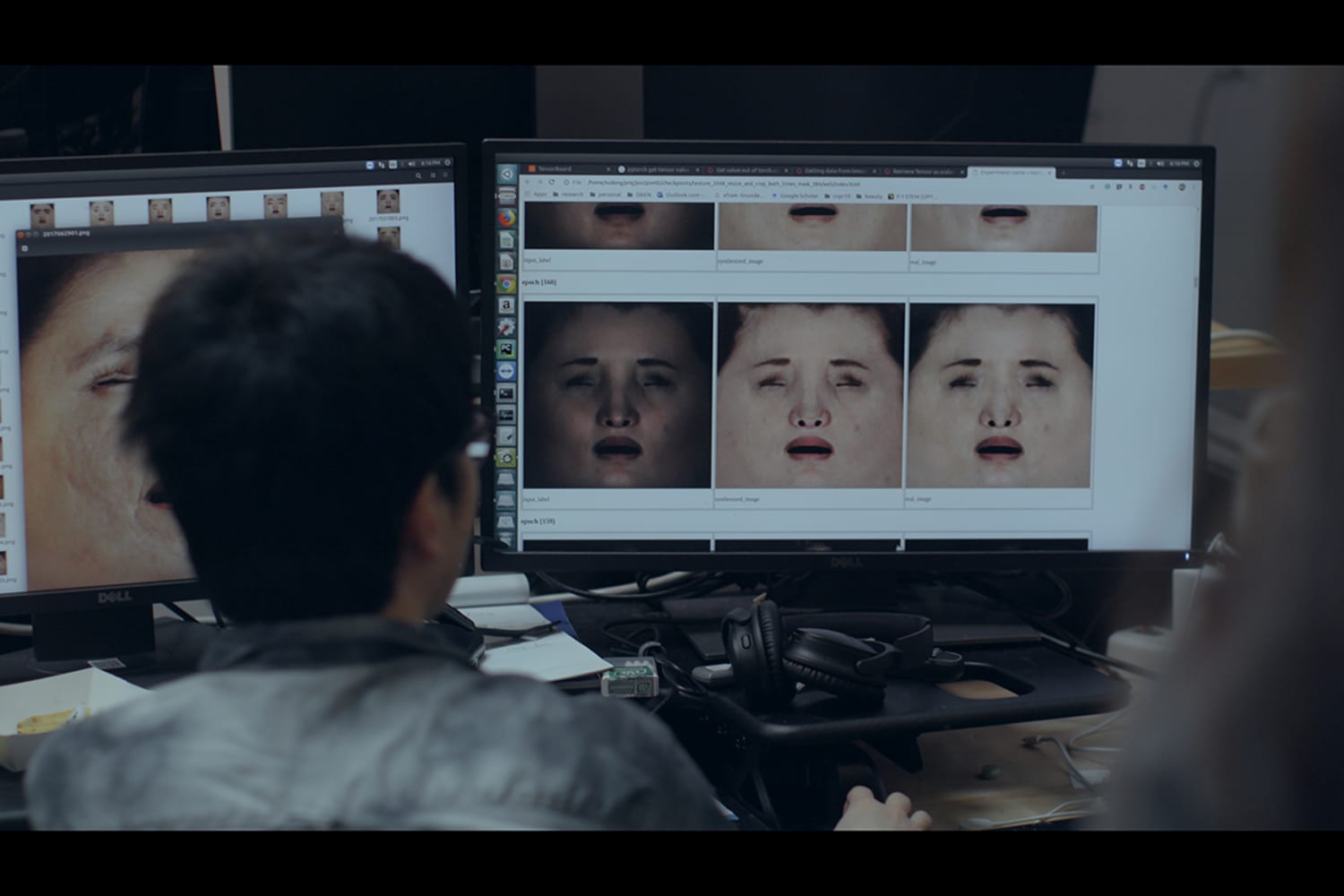

Yet the prospect of reviving likenesses of the dead – potentially without their consent – is an ethical minefield. Addressing this is the documentary Eternal You, which premiered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. Among the issues that grief tech throws up, the film examines how “the boundary between "real" and simulated life is becoming blurred,” and “what consequences…the end of finiteness [could] have for individuals and society.”

In a paper published in May in the journal Philosophy & Technology by AI ethicists at Cambridge University’s Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, its authors, Dr Katarzyna Nowaczyk-Basińska and Dr Tomasz Hollanek, set out the potential these “griefbots” could have. Hollanek told VML Intelligence that as there is currently a lack of research about this tech “we cannot know for certain what the impact of these emerging technologies will be on the grieving process at a societal scale,” he said. “What we do know is that grief is an especially vulnerable state. So when people decide to use griefbots or deadbots to alleviate its effects, the scope for harm, including manipulation, is enormous.” Hollanek added too that while big technology companies have “thankfully” been cautious about using grief tech, he noted that it’s “on their radar,” with Microsoft in 2021 having secured a patent for ‘re-creating’ specific people in the form of interactive avatars, ranging from fictional characters to the deceased.

Meanwhile, speaking from a psychological point of view, Dr Chloe Paidoussis-Mitchell, a chartered counselling psychologist, associate fellow of the British Psychological Society, and author of The Loss Prescription, suggests that avatars of deceased loved ones could “help promote healthy grieving if they are used with a 'grief aware' mindset,” she told VML Intelligence. “I.e. the avatar is [a person’s] aid to maintaining an ongoing heartfelt bond with the dead, but at the same time not relied upon as a tool to pretend the death hasn’t happened.”

Paidoussis-Mitchell added, it’s human contact that she believes is crucial to moving through the grieving process, noting that grief tech could lead people to “rely on technology to do the work that is best served through meaningful human connections…that acknowledge grief, and share in the process of it,” she said. “If everything is done by robots and avatars, my belief is that the bereaved will be left more disconnected from what nourishes their mental health,” with Paidoussis-Mitchell adding that she has “big concerns about the impact of such tools.”

The chance to have more time with a deceased loved one – even if it’s in digital form – is no doubt drawing both consumers and companies to this tech. Yet these realistic recreations of the dead represent thorny issues when it comes to how people process death, and myriad ethical questions for the companies who supply this tech.

Main image: Eternal You documentary. Image courtesy of Konrad Waldmann

Please provide your contact information to continue.

Related Content

Digital personality rights