Versace. Coach. Givenchy. Calvin Klein. Swarovski. Who’s next?

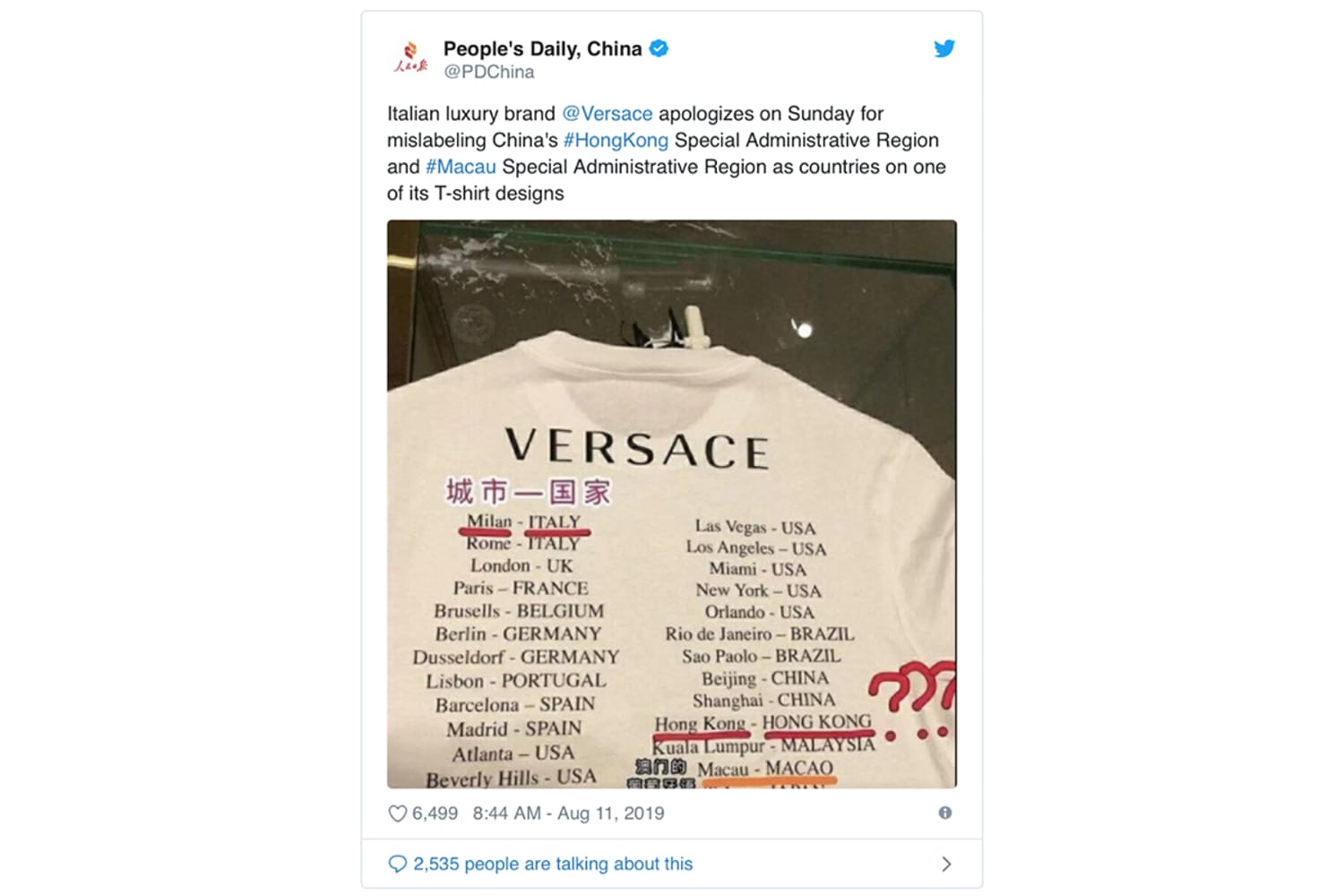

Last week, a spate of Western luxury brands got in trouble for selling T-shirts designed to resemble band tour merchandise, with store locations around the world listed on the back.

Versace. Coach. Givenchy. Calvin Klein. Swarovski. Who’s next?

Last week, a spate of Western luxury brands got in trouble for selling T-shirts designed to resemble band tour merchandise, with store locations around the world listed on the back.

Trouble was, Hong Kong and Macau—both special administrative regions of China as of 1997 and 1999 respectively—were not listed as part of China. With Hong Kong, a former British colony, now engulfed in anti-Beijing protests, that was an unforgivable provocation for many on the mainland.

As Chinese consumers scoured websites for similar listings, Swarovski and sports brand Asics were also drawn into the controversy.

Chinese consumers called online for boycotts. Versace’s China brand ambassador Yang Mi quit, as did Liu Wen, Coach’s country brand ambassador. The brands quickly issued apologies and pulled the offending items.

Via Instagram, Donatella Versace said she was deeply sorry. “Never have I wanted to disrespect China’s National Sovereignty, and this is why I wanted to personally apologize for such inaccuracy and for any distress it that it might have caused.”

The latest uproar underlines how China’s government and consumers are becoming more sensitive to perceived slights at a time of heightened geopolitical tensions. In addition to the Hong Kong protests against extradition, which began in spring 2019 and escalated from June, the US-China trade war that began in March 2018 has fired up nationalistic pride in China.

The response underscored the growing power of the luxury yuan. Bain & Co estimates that Chinese consumers account for a third of the global luxury market, which it valued at $260 billion for 2018, so brands have much to lose if they become the targets of China’s hyper-connected consumers’ nationalistic fervour.

“We are living in a digital world, where any local brand mistake can have an immediate impact,” wrote Daniel Langer, CEO of brand consultancy Équité, in Jing Daily.

Luxury brands are not the first to feel the effects of China’s wrath.

In January 2018, China blocked access for a week to the Chinese websites of hotel chain Marriott for listing Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan as separate countries. China governs Tibet as an autonomous region. And while Taiwan has a democratically elected government, China regards it as a renegade territory.

In 2017, China banned group travel to South Korea due to the latter country’s decision to install a US-backed anti-missile system, slashing Chinese tourist numbers to this previously popular destination.

What’s interesting is that consumers everywhere, not just in China, are becoming more political, and brands can find themselves caught in the crossfire.

The flurry of T-shirt apologies did not please everyone. “Donatella, be brave and don’t apologize,” was one response to Versace’s Instagram statement. “The people of Hong Kong are suffering.”

Even before the T-shirt controversy subsided, the star of Disney’s live-action remake of animated film Mulan sparked another.

Chinese actress Liu Yifei, an American citizen, reposted on Weibo a comment from the pro-Chinese government People’s Daily newspaper supporting Hong Kong police, who have been criticised for their violent handling of the peaceful anti-Beijing protests. Before long, #BoycottMulan was spreading on Twitter.

The episode underscores how brands are increasingly having to navigate uncharted political waters, while balancing different stakeholders.

This is in large part because consumers increasingly expect brands to take a stand. “The Political Consumer,” a 2017 JWT Intelligence report, surveyed 1,001 Americans and found that 44% say they typically only purchase from brands that stand for what they believe in, with that sentiment strongest among millennials and generation X.